Like the rest of this project, this page provides a “window” into a particular aspect of the property’s history and the people involved with it. It is not a comprehensive report on the colonial connections of the house, financial or otherwise. Instead, it focuses on three family interests and a few lines of enquiry within that, of particular relevance as these connections are mentioned in the text elsewhere.

Bristol was one of Britain’s three principle cities involved in the transatlantic slave trade. Many of its residents were also involved in the plantations where the enslaved people worked, and the many businesses connected with them or benefitting from the wealth derived from these enterprises. Individual family links to slavery are often quite complex but its importance to the city’s economy in the 18th and early 19th century cannot be underestimated.

Rather than continually refer back to these legacies in the text whenever land purchases, gifts, property improvements or any other developments are concerned, they are mentioned here instead.

While many properties in the city can be very directly linked to the proceeds of industries that used slave labour, the connections of the house we are concerned with is less obvious at first glance but nonetheless important to mention. This is doubtless the case with many other properties and institutions in the city, which are more likely to have “invisible” or less easily discerned connections than the property’s listed on the UCL database as having a documented link with plantations – just over 200 in and around Bristol at the time of writing.

Way/Smyth – Arthur Edward Gregory Way lived in the property 1880-1919. He lived off income from the Ashton Court estate and was able to purchase the property due to an inheritance that was, in all probability, in large part comprised of funds derived from the estate. The Smyth family, which the Ways married into at least twice, owned the land pre-build from 1605 to 1874. In Historic England’s “Slavery and the English Country House” (2013), Madge Dresser highlights the following:

The renovation of Ashton Court near Bristol came after the marriage in 1757 of John Hugh Smyth to the Jamaican heiress Rebecca Woolnough. The marriage settlement of £40,000 comprised properties in England and Jamaica (including the Spring plantation in Jamaica) and substantially improved the fortunes of the Smyth estate. Indeed it was estimated by one local historian that the profits made by Sir John Hugh Smyth from the Spring plantation and the sale of its sugar amounted to some £17,000 over the period 1762–1802.

However, subsequent research suggests that the family’s association with the Atlantic slave economy pre-dates this marriage, as Sir Hugh Smyth’s father, Jarrit Smith, a Bristol solicitor, was also a member of the Bristol Society of Merchant Venturers – the elite body which actively lobbied on behalf of Bristol participants in the African, American and West Indian trades.

See also, from Friends of Ashton Court Mansion: Summary of the Ashton Court Smyths and the Slave Trade.

Cave – Ada Louisa Cave married Arthur E G Way and lived in the property 1888-1936. After her husband’s death in 1919, she owned the house for another 17 years making her the longest standing occupant of the house. The Caves were a very wealthy Bristol family, with interests in banking, glass manufacturing and shipping. Her grandfather, John Cave of Brentry (1765-1842), is listed by UCL as a “claimant or beneficiary” of the scheme that compensated enslavers following abolition (Slavery Abolition Act 1833).

The Abolition Act of 1833, abolishing slavery in the British Empire, came into force on 1st August 1934. No enslaved people received any compensation for their suffering. The British government paid out around £20 million to the enslavers (the owners of the plantations). Based on 2013 values, the compensation payment amounts to around £16 billion today, approximately 40 percent of the Treasury’s annual income for 1833.

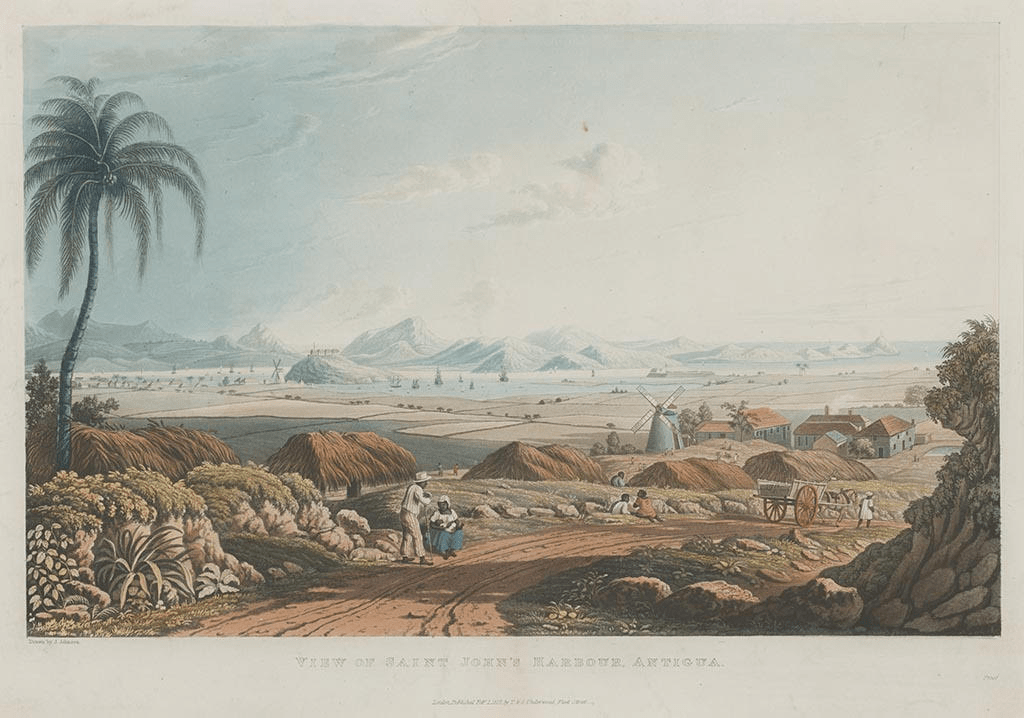

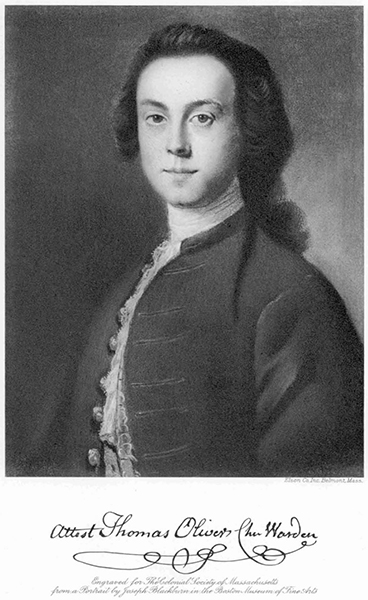

John Cave’s first wife was Penelope Oliver (1771-1815), the daughter of Thomas Oliver (1733-1815), who had owned the Friar’s Hill plantation on Antigua and derived a considerable income from it. In November 1835, a compensation claim against the Friar’s Hill plantation (137 enslaved people) netted six members of the family £1,984. This was “Antigua 37: Friar’s Hill” claim, which had both Ada’s grandfather, John Cave, and her grandmother, Penelope Oliver as beneficiaries. As the dates indicate, Penelope died young and was laid to rest at the age of 44 at St’s Mary’s Church, Henbury, Bristol.

Sources suggest that Friar’s had 206 enslaved peoples working on the plantation in previous years. It is worth noting, if it is not already obvious, that although the database provides a figure strictly for the compensation payout, similar figures are not as readily available for the less tangible but substantial ways in which the Caves will have benefitted from plantation ownership historically.

The Antigua Sugar Mills website hosts a helpful page on the Friar’s Hill site, noting Thomas Oliver’s 1790-1829 ownership of the plantation. You will also see that Vere Cornwall Bird, the first Prime Minister of Antigua, owned the plot 1970-75. Neither the plantation house, nor any of the ancillary buildings or sugar mills survive. Regrettably, as the website itself notes, nothing appears to remain that can tell us much about the lives of the enslaved people who worked on this estate.

Thomas Oliver’s former home (Elmwood House) is itself undergoing a historic reassessment at the time of writing (see Where Bacow Lives, Slaves Once Did, Harvard Crimson, 2020). Also known as the Oliver-Gerry-Lowell House, it was was originally built for Oliver during his time as the last Royal Lieutenant-Governor of the Province of Massachusetts Bay and would go on to house a succession of notable residents including an American Vice-President and a man who would give his signature to the American Declaration of Independence. It was briefly used as a hospital of by the Continental Army, following Oliver’s resignation. The house that stands today was once part of a 100-acre estate but more recently was donated to Harvard University in 1962 and is now used as the residence of its incumbent president.

Thomas himself would end up in Bristol having supported the British side in the American War of Independence. The details of his probate [PROB 11/1576/61] are available on UCL’s Legacies of Slavery database, where we can trace the dispersement of his will to John Cave. Having earmarked his Park Street address (and its furniture) for his unmarried daughters [Frances Oliver, Lucy Tobin (widow of Henry Hope Tobin Esquire), Harriet Watkins Oliver and Emily Freeman Oliver], and any remaining dues from Antigua to Harriet, he hands his remaining estate to his sons in law [Joseph Rogers, John Cave and Charles Anthony Partridge] to manage in trust. The “residue of the net proceeds of my residuary estate” was to be divided up equally amongst his daughters [including Penelope Cave].

Thomas is buried at St Paul’s Church, the striking building on Portland Square which is now owned by the Church’s Conservation Trust. Friar’s Hill came under the ownership (from 1821 at least) of Captain Henry Haynes RN (1777-1838) who married Thomas Oliver’s daughter Harriet Watkins (1776-1838) at St-Augustine-the Less church on 3rd July 1815. In case you are wondering where this is – the church was bombed during WWII, suffering mostly fire damage to the roof and demolished in 1962.

Their marriage settlement, with specific respect to the Antiguan plantation and the people that were enslaved there, is available to view in the Manuscripts Reading Room at Cambridge University Library and dates from the year of their marriage.

John Cave was a founding partner of Cave, Ames and Cave (1786-1826), also known as “the Bristol New Bank”, which would later become a constituent part of NatWest. Two other partners, Thomas Daniel and Richard Bright of Ham Green were involved in the triangular trade and plantation ownership on a considerable scale. Thomas – and his brother John Daniel – claimed and won compensation for 4,300 enslaved people working their plantations. This amounted to £135,000, around £9 million in 2017 values. This made them two of Britain’s biggest beneficiaries from the slavery abolition scheme.

The banking entity changed names quite a few times, in the manner of banks of this era. It features in NatWest’s “Heritage Hub”, which provides a helpful list of name changes over the years, prior to its purchase by Elton, Baillies, Tyndall, Palmer & Edwards. After this point we see it recognised first as Elton, Baillie, Ames, Baillie, Cave, Tyndall, Palmer & Edwards (1826-37) and latterly as Miles, Cave, Baillie & Co.

Name changes at Cave, Ames and Cave (1786-1826), via NatWest

Ames, Cave, Daubeny & Bright 1798-1800

Ames, Daubeny, Bright, Cave, Daniel & Ames 1800-1806

Ames, Bright, Cave, Daniel, Ames & Daubeny 1806-1813

Ames, Bright, Cave, Daniel, Ames & Ballard 1813-1820

Ames, Bright, Cave, Daniel, Ames & Bright 1820

Bright, Cave, Daniel, Ames & Bright 1820-1821

Cave, Daniel & Ames 1821-1822

Cave, Ames & Cave from 1822

John Cave’s portrait hangs at the National Trust’s Basildon Park site, where he is depicted wearing his uniform from the “Bristol Troop of Gentlemen and Yeomanry Cavalry”. This is not due to a direct connection with the family and Basildon and its owners to the best of my knowledge but the result of a bequest to the trust from the Caves in the 1970s.

As mentioned in the text – the primary family seat for the Caves at this time was Brentry House (later Brentry Hospital and now known as Repton Hall).

Wills – The Wills family never owned the property or lived there but were important in the development (or not-too-extensive development) of the local area. Their former houses (Bracken Hill House and Burwalls House) as well as donations of land to the National Trust are mentioned throughout this text without referring to the use of enslaved people by the tobacco industry so it is noted here instead. This short summary from Bristol Museum (Tayo Lewin-Turner, Madge Dresser, Sue Giles) provides a helpful overview:

The Wills family grew rich off the tobacco industry in the nineteenth century from their family company, W.D & H.D Wills. Although much of the Wills’ wealth would come after the British abolished the slave trade in 1807 and slavery itself in 1833, and although members of the family supported the pro-emancipation MP for Bristol in 1830, the family had long-standing ties with and profited greatly from the enslavement of Africans.

Henry Overton Wills III used slave-produced tobacco from the USA to supply his business. This source of revenue was not abolished until the loss of the Confederate States in the American Civil War in 1865. The Wills’ use of slave-produced tobacco allowed the family to become the great philanthropists for which they are now remembered.

In the Leigh Woods context this philanthropy specifically involves: the 1909 donation of 80 acres of land to the National Trust (Nightingale Valley and Burwalls Forest) by George Alfred Wills and the 1936 donation of 60 acres by Walter Alfred Wills.

—

Originally under “The Way Era”, 2019, subsequently “Notes” 2020, moved to this page in 2022 and updated as per Revisions under WordPress.

Coates, Ashley. “Legacies of Slavery – A History of a Bristol House.” A History of a Bristol House, ahousehistory.com, 10 May 2022, https://ahousehistory.com/legacies-of-slavery/.