The Ways owned the property for the greatest length of time, and by some margin. Between Arthur E G Way and his wife, Ada, they owned the property for 56 years. As we shall see, the Ways had married into the Smyth family of Ashton Court twice and Arthur Way was able to live off income from the estate. So to some extent the house can be seen as a continuation of Smyth ownership, which began in 1605 when Sir Hugh took over what was then Leigh Down, with a break of just six years when an outfitter by the name of Thornley built the house. This is covered in the previous chapter.

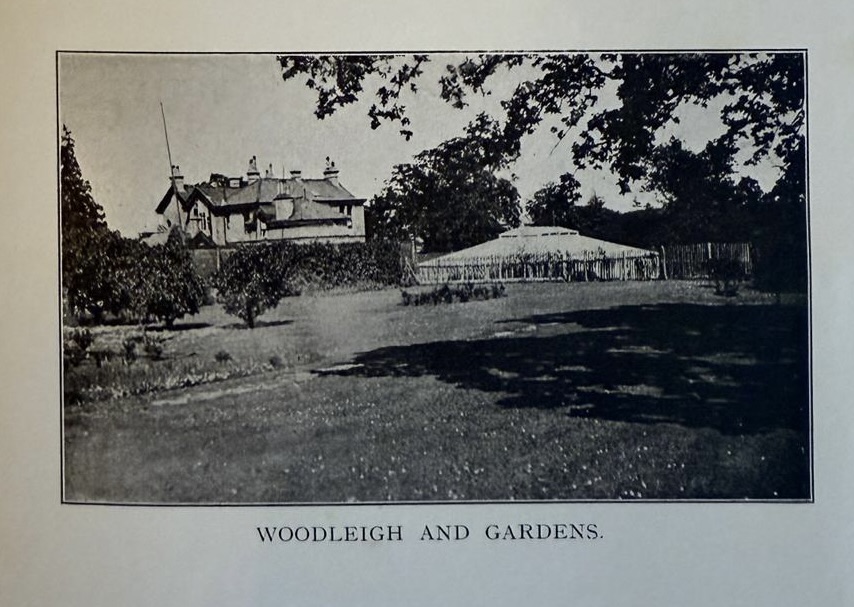

This was also the time when the property was at its grandest, and strangest. Arthur Way (who also called himself Greg Way and appears in the City archives as such) had a long standing interest in gypsy culture and would pen a first person fictional account of gypsy life under a pseudonym in 1890. He also had a room built for boxing and entertaining the gypsies he knew personally. The house appears to have taken the form of a miniaturised country estate within a suburban Bristol setting. Roughly 0.7 acres was left as woodland, kennels were installed for around six dogs. Two grooms were employed to look after (probably) as many as six horses, giving rise to the idea that the property was a hunting lodge. The grooms formed part of a household staff of 5-7 people over this period, housed in a separate property, now demolished, at the end of the plot.

This period also saw a considerable decline in the fortunes of Ashton Court itself and this would have impacted the Ways very directly. The mansion of 1880 would have been at the height of its Victorian pomp, Greville Smyth having been the second richest man in Somerset at the time he took over (Bantock’s assertion). By 1936, the estate was just ten years away from running out of money completely. Arthur and Ada mirrored the largesse of their cousins but by the end of their ownership, their “mini” estate in Leigh Woods would follow a similar path to Ashton Court – downsizing and shedding staff by the time it came up for sale.

A Tangled Web – Connections in Victorian Bristol

Arthur Edward Gregory Way (1850-1919) purchased the house in January 1880 for £2,611.50, around £172,000 today. Thornley retained a “farm rent” of £30 per year, which he subsequently sold on. It is safe to assume Way and his brother Claude Greville Way were the first occupants of the house.

The Way family has an intriguing history going back many centuries, with the first recorded Way having been yeoman of the guard to Henry VIII. Arthur Edward Gregory Way was the son of Arthur Edwin Way (1813-1870), the MP for Bath (1859-1865) and the steward (a form of household and business manager) at the Ashton Court Estate 1851-57. A local historian, Dr Michael Marston, says that Arthur Edwin Way was a successful steward who did much to improve the fortunes of the estate in the Mid-Victorian period. It was also Arthur senior who had overseen the original plans for developing Leigh Woods into a town in its own right back in 1864 and was appointed the guardian of Greville Smyth and held his funds in trust when he inherited the estate at the age of just 16.

Arthur E G Ways’s great grandfather was MP for Bridport and great great grandfather a director at the doomed South Sea Company. The many branches of the family tree shoot off in interesting directions which are not worth going into detail here. There is a 1913 book “A History of the Way Family” for anyone who wants to delve into this further.

The branch of the Ways we are concerned with were deeply embedded with the Smyth family both in the running of the Ashton Court estate and through two marriages. Arthur Way’s grandfather, Benjamin Way (1770-1834) married Mary Smyth (1778-1850) in 1798 and Arthur’s first cousin Sir John Henry Greville Smyth (1836-1901), married his first cousin Emily Frances Edwards (née Way), the widow of George Oldham Edwards, in 1884.

Sir John Henry Greville Smyth (better known just as Greville Smyth) inherited the Ashton Court estate in 1852 at the age of 16 and is said to have been the second richest man in Somerset, with Ashton Court drawing an annual income of £27,000.

This means when Arthur E G Way was at the property, both the “lady of the house” and the “head of household” at Ashton Court were his first cousins. Edgar Way, Arthur’s uncle, took over the running of the Ashton Court Estate from Arthur’s father and was the estate’s steward when Arthur lived at the property we are concerned with.

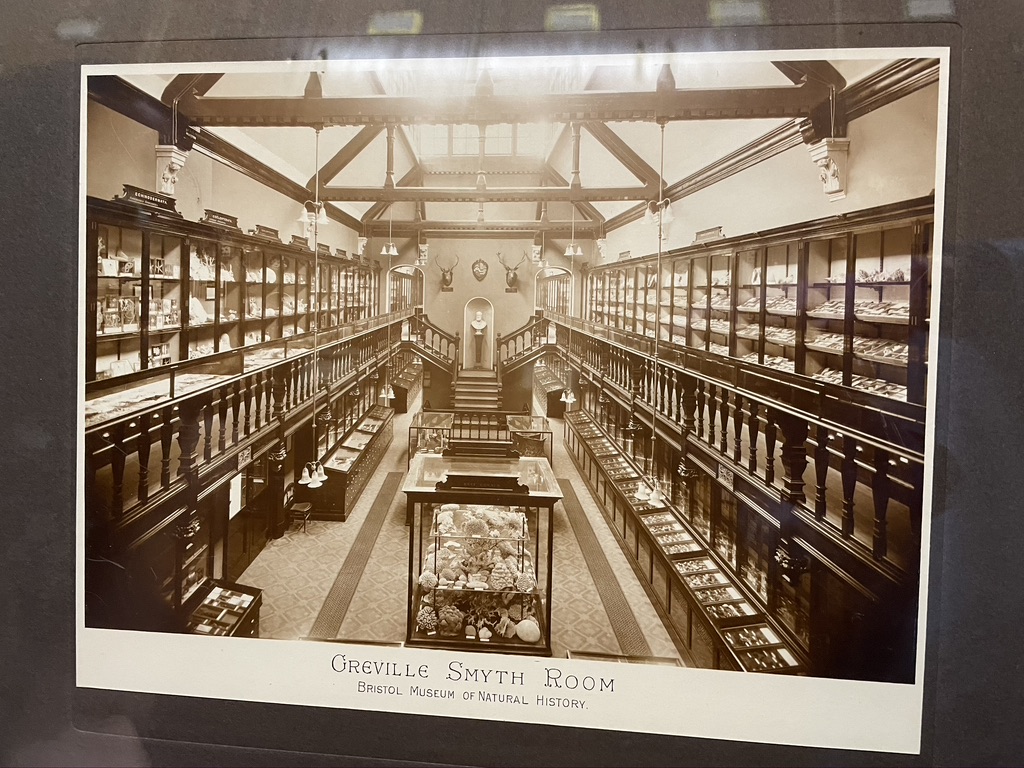

Greville Smyth was a notable Victorian naturalist famed for his large collection of taxidermy and other natural history specimens, most of which were kept in a private purpose-built museum at Ashton Court. It was one of the best collections in the country, and easily the largest assembled in the West Country. He acquired two eggs of the (as of 1844), extinct great auk, some of the rarest and most expensive preserved specimens a Victorian collector could get his hands on.

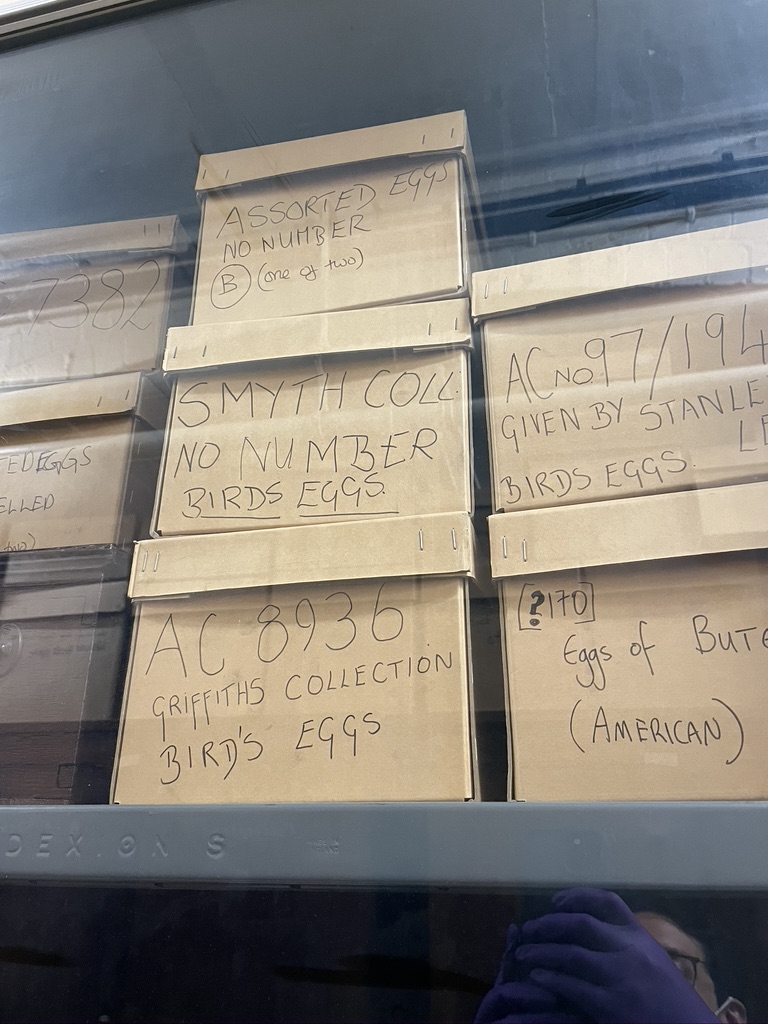

Above: Greville Smyth’s great auk eggs. Donated to Bristol Museum & Art Gallery (via its predecessor institution, Bristol’s own Natural History Museum) by his wife, Emily. These are kept in a safe and the photographs date from a 2021 trip I took to the museum’s basement. Dame Emily was a major benefactor to the museum, which ultimately named two huge wings after her and Greville, only for both to be bombed during WWII. Most of their immense collection is below ground but there are some pieces available to see on the first floor, such as the two golden eagles. The purpose-built museum at Ashton Court also no longer stands – this is where Audley Redwood is now.

Leigh Woods Land Company signatures on first deeds:

George Oldham Edwards

Isaac Allen Cooke

William Henry Powell Gore-Langton DL JP

William Henry Harford

George Oldham Edwards (Emily Way’s first husband) was a director at the Leigh Woods Land Company and his name is on the first deeds of the house on behalf of the firm. Edwards was a local banker who lived at Redland Court (latterly now Redland High School for Girls and soon to be flats) and had been Sheriff of Bristol in 1857.

Emily Smyth had (according to local historians such as Anton Bantock MBE), been having an affair with Greville before the death of her husband, and bore an illegitimate child. Esme Smyth, the final owner of the estate before it was sold to the council, was therefore christened Esme Edwards. As an aside: Emily Smyth is also believed (by Bantock and others) to have had an affair with the then Prince of Wales during her marriage to Greville.

There is no particular need to detail the lives of the Smyths and Ways at Ashton Court here as this is already well covered in Bantock’s volume on Ashton Court and elsewhere.

Another name on the first indenture is that of William Henry Powell Gore-Langton DL JP, a banker and a Conservative MP for Somerset Western at the time the deeds were signed. He too appears to have been a director at the Leigh Woods Land Company. The Gore-Langtons pop up everywhere and I won’t go into too much detail here. It is worth reflecting that Arthur Way Senior (who had overseen the more expansive plans for Leigh Woods) was MP for Bath at the same time, which goes some way to show how business and politics were allowed to operate concurrently in Victorian England, although it should also be noted that both MPs shared their seats with someone else, providing time for pursuing their business interests. There was no salary for MPs at this time.

William Gore-Langton had inherited the right to mineral extraction at the bottom of Nightingale Valley and needed to be “bought out” by Greville Smyth before the sale of Leigh Woods to the Leigh Woods Land Company. This was achieved by providing William with the rights to extract minerals from a different part of the Ashton Court estate.

One W H Harford has also signed the indenture on behalf of the Land Company. This is almost certainly one of the two William Henry Harfords that were around in Bristol at this time and part of the dynasty that at one point owned (what we now call) the Blaise Castle Estate and pioneered the Bristol Brass Company – once the biggest producer of brass in Europe. This could feasibly be the 1829-1903 W H Harford or his father, 1793-1877, though probably the former.

Isaac Cooke (again, the junior) is another signatory for the Company. Isaac Allen Cooke followed his father into a solicitor’s practice in Clifton and was Bristol’s Mayor in 1857. Greville Smyth would have been Sheriff at the same time.

Arthur Way Junior followed his father and cousin in attending Eton College. He graduated from Christ College, Oxford in 1871 and became a student of the Inner Temple in 1872. Arthur Edwin Way died on 19 September 1870 at his house (Ashton Lodge), then part of the estate and near the estate offices which are still labelled as such on the corner of Lodge Drive in Long Ashton. This house no longer stands.

The 1871 census has Arthur E G Way living with his mother (Harriet Elizabeth Way) and brother in Clifton Down. Harriet Elizabeth Way died, aged 61, on 7 September 1879 at Rownham House, also part of the Ashton Court Estate. She left an estate valued at £30,000, providing enough funds for Arthur Way to purchase property in 1880 for £2,611.50 at the age of 30.

Way married his first cousin on the other side of the family, Ada Louisa Cave, on 29 May 1888 at St. John The Evangelist, Clifton. Ada’s grandparents on the Cave side (John Cave of Brentry and Penelope Oliver) owned and lived at Brentry House, designed by Humphrey Repton and today known as Repton Hall. A more detailed overview of this side of the family, and its connections with slavery, is here.

Repton is also responsible for much of the remodelling of Ashton Court and Paradise Bottom in the Forest England section of Leigh Woods. Today a large portion the grounds of the property are open parkland known as Royal Victoria Park while the main property has been converted to flats following a long period as a hospital. Both are Grade II listed.

Ada was the first child from the second marriage of John Cave’s youngest son William Cave. He married Louisa Frances Butterworth in 1850 (the side of the family that connects Ada and Arthur as first cousins).

The Victorian Zenith – (1880 to 1901)

One of the distinguishing features of the Way’s time at the property was the size of the household staff, larger than a house of this size could have needed at the time. It then consisted not only of the house itself, but of the three plots behind the house, affording space for a significant household staff in their own dwelling house and room for stables.

In the 1881 census, the 30-year-old Way was the head of a household which included his brother, Claude Greville Way, Annie Leppiatt (servant), Alice M. Brown (servant), Frank Salter (footman), Henry Vizard (groom), James Bishop (groom). A groom in this context refers to someone who looks after horses, having two on payroll suggests there would have been a fair number of horses as today one groom would be expected to maintain around 3-4 horses. The other North Road houses managed to get by with less.

Over at Ashton Court, his first cousins were living the full-blown Downton Abbey lifestyle. The 1881 census shows seven Way cousins living in the main house, some employed in the service of the estate, others not. Fully 18 people living at Ashton Court were employed in its upkeep in one way or another.

Back at Woodleigh, a system of sprung servants’ bells was in operation at the house, even though electric bells had started to be installed in large houses from the 1860s onwards. Part of the pully system for these bells is still visible in the attic. An electric push button on the floor in the dining room was in action up until the mid 2000s, allowing diners to ring bells without having to even move from their seats.

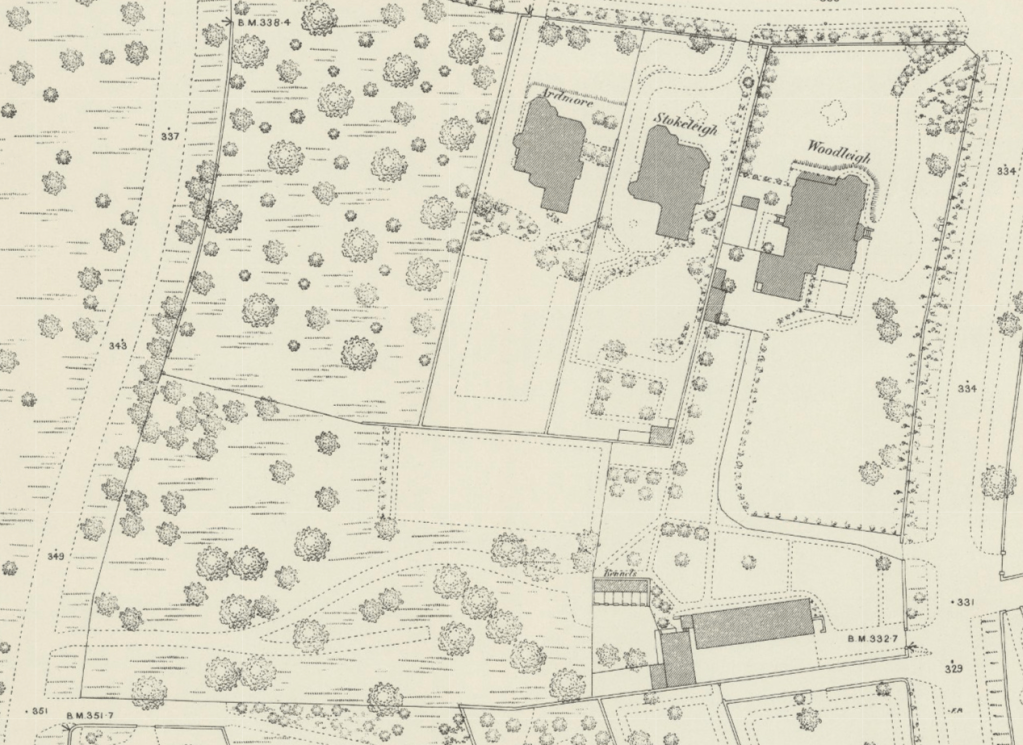

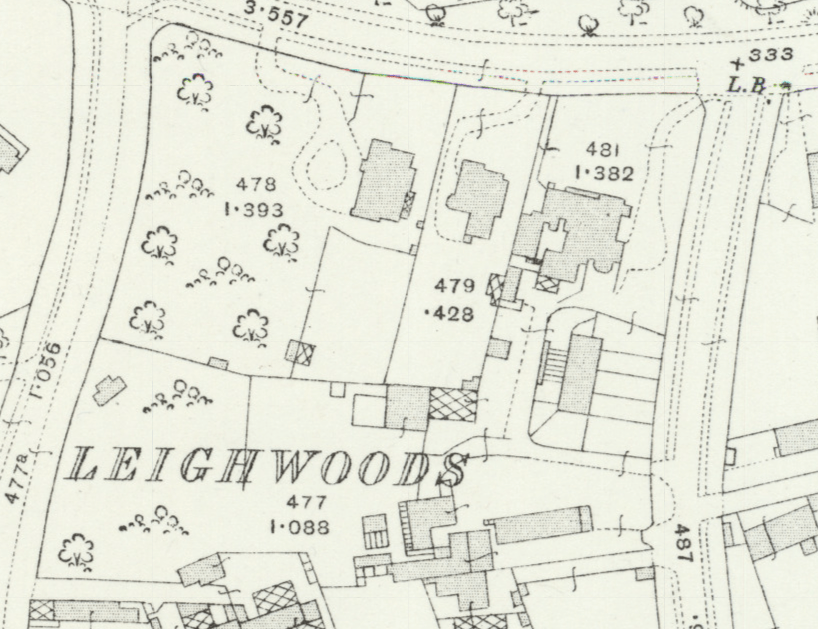

From historical maps we are able to see the full extent of the Way property at its Victorian zenith. Based on the Bristol Corporation’s Town Plan map (1879-1888), we can see that the three plots purchased by Thornley were still three distinct areas.

The “house plot” included a fountain in the front garden and a lawn at the back along with a series of outbuildings. We can probably assume these are the same greenhouses and log stores that were demolished in the early 2000s. South of this plot was the working part of the estate. It contained a house (possibly two) for the staff, a series of kennels and what looks like areas for working the land, possibly growing vegetables. From this map it is possible to discern with some certainty that the kennels had capacity for around six dogs. In all, there are around seven buildings separate to the main house, the majority of which no longer stand and would today be separate from the plot.

The third plot, to the west of the estate, seems to have been left as woodland, with a series of paths working through it. There is an obvious clearing roughly where Lake House now stands – perhaps a paddock for the horses. Stokeleigh, to the west of the house, still stands, but Ardmore, once the home of the Harvey family (of sherry fame) is one of North Road’s “lost houses”.

An OS map from the period seems to bear out the same details almost exactly. A later map (OS 1894-1903) shows a new building in the woodland area and several in the working area. A large building has now appeared in the middle of the lawn, this is assumed to be a greenhouse, which stood until at least 1949. It does seem as though a building emerged in the late 19th century on the site where the Garden House now stands. This is now a residential dwelling.

Arthur’s brother Claude Greville Way lived at the house for many years and would follow in the footsteps of the military side of the family, serving as a Captain in the South Staffordshire Regiment (38th and 80th Foot), he was at one time posted to Gibraltar. There is a local rumour that the stone archway that now stands on the grounds next-door was used as a rest for a gun used by a former occupant of this house with military connections. This may or may not be true but if it is, that person is likely to be Claude. Sadly, it looks as though Claude died at the age of just 39, on Park Lane in London. Arthur E G Way was the sole executor.

The 1891 census shows that Salter (previously the footman) had now become the butler, probably the first, at the age of 31. George Harvey and George Harding were grooms, Sylia Fry was the youngest employee at 17 years of age and worked as the kitchenmaid. Anne Willis was the housemaid. Arthur’s wife was also on the 1891 census.

At some point in this period, the very smart Victorian postal pillar box appeared on the edge of Bannerleigh Road. This is of a design dating from 1889–1901 from Handyside & Co of Derby & London and is the smaller of their two pillar boxes from this period. It, and the very attractive VR cipher, survives in place to this day.

Aristocrat By Day – Gypsy By Night: The Strange Case of Arthur Way

Exactly how Way’s life was funded is not obvious but it is clear that he had considerable family wealth and various investments, probably closely tied up in the Smyth’s businesses and directly derived from the Ashton Court estate. The census data seems to bear this out – with entries simply saying “private means” or “income from dividends”, a position mirrored by at least three other Leigh Woods residents at that time. Many years ago, it was suggested by a local historian (Dr Michael Marston, church warden at St Mary’s) that A E G Way had been involved in African gold mines, though this is yet to be substantiated. It would certainly explain the largesse with which the Ways were able to live for the best part of half a century.

One of the only pictures we have of Arthur E G Way from this time shows his on a shoot with Greville Smyth and – amongst other people – the celebrated imperial war hero, General Sir Redvers Buller VC. He appears in many of the Ashton Court photographs from the period, most of which are offline and can be found in the council’s archives.

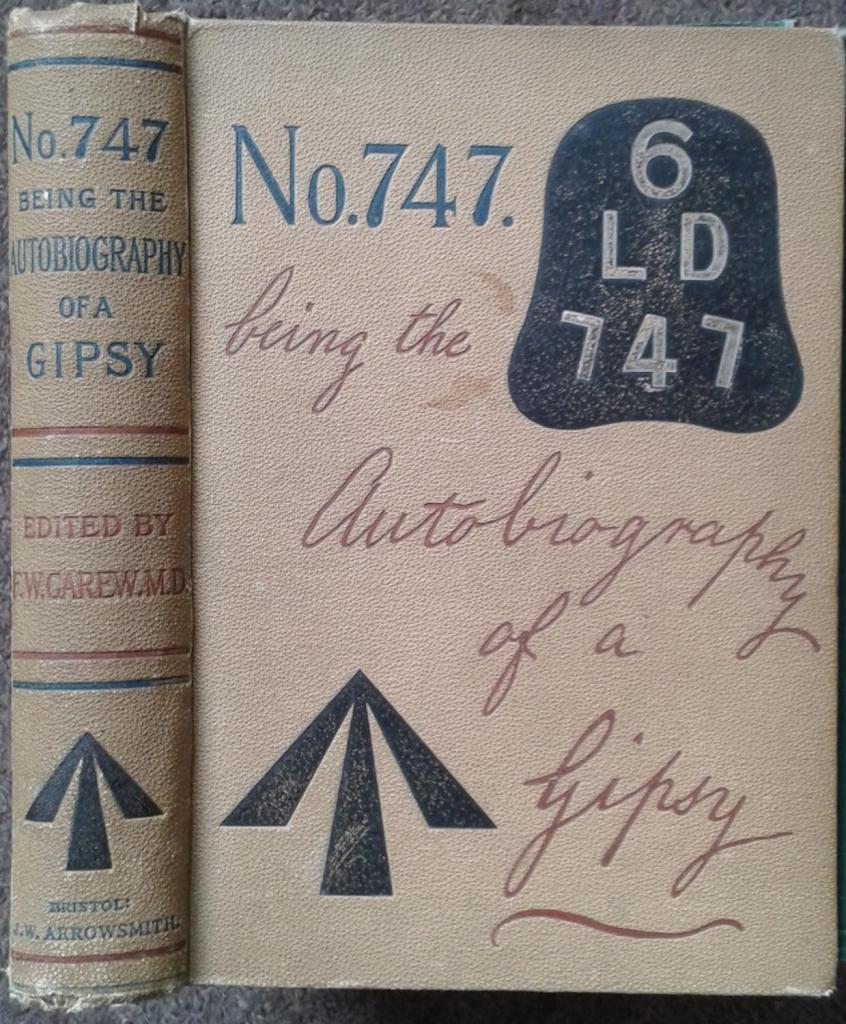

Curiously, newspaper records from the time show that Way tried to register at least two patents, one for “an improved lamp” (approved) and another for “improved motor car”. Even more bizarrely, a book entitled “No. 747 Being the Autobiography of a Gipsy” was written in Bristol by one Arthur Edward Gregory Way in 1888.

According to Henry J Francis, of the Journal of the Gypsy Lore Society (Way was a member of the Society), Arthur Way was deeply interested in English gypsy and Romani culture, and took to spending time with gypsies, and was close friends with many groups.

The book was published by the Bristol publishing house J W Arrowsmith of Quay Street and was written under a pseudonym (F W Carew MD as editor and Samuel Loveridge as an imprisoned gypsy). It is a fictional account of a West Country gypsy and draws on real life events which happened in and around Bristol and Somerset. Francis and the Gypsy Lore Society published an extensive review of the book in 1954 and asserts that the work is under-appreciated and represents one of the best literary interpretations of gypsy culture at that time.

“It attracted very little notice at the time, though it was, and still remains one of the most notable of books dealing with the life and language of the English Romanies”.

Francis continues…

“It is our opinion that that portion of the book dealing with Gypsy life has never been surpassed for vividness and truthfulness, and that, for these reasons if for no others, a knowledge of its existence should be more widely known amongst Gypsiologists”

It remains in print today, in the British Library’s Historical Editions collection, and is still printed under the fictitious name of F W Carew.

According to Patricia T. O’Conner and Stewart Kellerman, the earliest Oxford English Dictionary citation of the term “nark” to mean a policeman comes from this book:

“If you don’t turn up my fair share, I’ll put the narks upon you. S’elp me never, I will.”

John Harris Stone, the writer of “Caravanning and camping out” (1914) joined the Gypsy Lore Society in celebrating the work, writing:

In addition to these two novels, there is only one that can be recommended because it depicts Gypsies as the author saw them with his own eyes, and not as he had read about them, or as he conceived they ought to be. It is called No. 747 being the Autobiography of a Gipsy (Bristol, 1890), was published, under the pseudonym ” F. W. Carew, M.D.,” by Arthur Edward Gregory Way, and can generally be bought for about four shillings and sixpence.

The Gypsy Lore Society also tells us that Way used a room in the house for “pugilistic activities” – i.e. boxing and hosting meetings with “the fraternity”. This was almost certainly the billiards room and we are told that Way himself would engage in the boxing here. The two roof hatches are attached to a pully system which would have allowed them to be opened just enough allow for ventilation.

The use of the room as a sort of “den” (and latterly a garage) perhaps explains why, up until 2005, this room was not connected to the rest of the house. Way’s use of the room probably also explains the strange positioning of the windows. There would have been five originally, all are small and above head height. The explanation for the room given by Savills in 2003 was that it was a room for hanging dead animals (part of the mistake of believing the house had been a hunting lodge).

The Henry Francis’s interpretation was that Way may have tried to hide his interests in gypsydom from some of his family and friends. Oddly, he also did not reveal that he was the author of his own work to the society and appeared to have shun later approaches from members interested in his work. Francis appears to have gone on a similar journey to me back in 1954, unable to find anyone who knew anything at all about Arthur Way. The Society did at least managed to ascertain from Way that the book was based on gypsies that he knew in person.

Unknown to the occupants until this research was carried out, this is probably the single most surprising discovery covered in this house history. I personally had used the room for years (including as an isolation zone during the Covid-19 pandemic as well as a study) and found out about Way’s original use of the room whilst I was sitting in it.

“At his home in Leigh Woods, he set apart a building for pugilistic exhibitions and ‘the fraternity’ was always welcome. And Way himself was not adverse from putting on gloves with the locals, according to information given to Ivor Evans, when in Bristol in 1951.” [Journal of the Gypsy Lore Society, Volume XXXIII an essay by H J Francis, 1954].

One of the stories in Way’s book is about a man becoming estranged from his family as a result of his interest in gypsy culture and the society has speculated that this may be semi-autobiographical. Nevertheless, Arthur (or Greg Way, as he was known by friends and is referred to in some of the estate archives, and on the census results) can be seen in pictures attending his cousin’s hunts on their grounds at Teddington (Somerset), including one image where he is standing beside the imperial war hero General Sir Redvers Buller VC GCB GCMG. Way was probably a Victorian gentleman eccentric in the typical sense, capable of taking part in shooting parties one day, and then boxing with gypsies in his purpose-built boxing ring the next.

Having thought I had discovered all I reasonably could about A E G Way, I happened upon another curious twist in his story whilst in the Clifton Library. In his 1980 publication, ‘The Inside Story of the Smyths of Ashton Court’, Anton Bantock has Way as the steward at the Ashton Court estate in 1917. He would have been following in his father’s footsteps and presumably Edgar Way was no longer in the picture. It is one of my greatest regrets that I started this work after Bantock passed away, no doubt he would have been a great help.

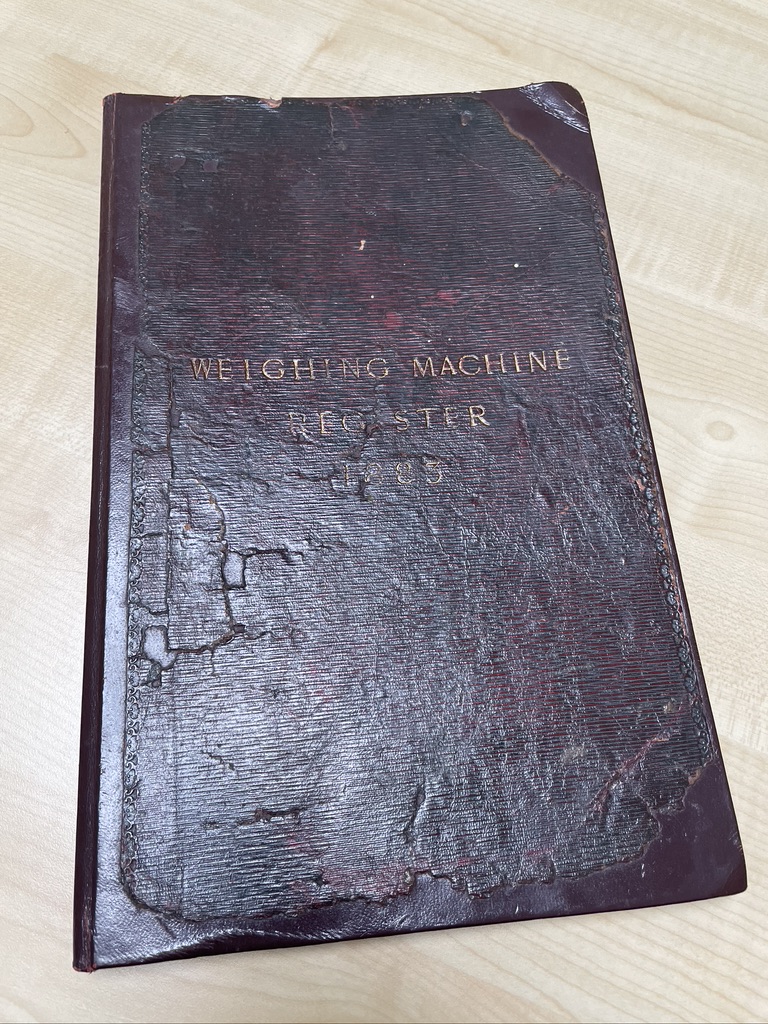

He popped up again in one of the most eccentric corners of Bristol’s historic environment – a record book charting the weights of members of the Clifton Club. Dating from 1883, the book has been sitting on top of a fireplace near the club’s reception at 22, The Mall for well over one hundred years.

The book accompanies a “weighing machine” (scales), donated by club member Sholto Vere Hare (1820-1900) in 1882. Hare was a partner in John Hare & Co Ltd (floorcloth and paint manufacturers), a common councillor for Redcliffe, a Mayor of Bristol (1862) and President of the Dolphin Society (1871).

The scales were produced by Bristol-based manufacturer Bartlett & Sons and it appears to be an adaptation of one of their agricultural sack scales. It was restored and modified by the Bristol Scale Co in the 1940s.

Hare also donated the weights “register” – which has weights of club members going back to 1883. His name is the first in the record book. This book represents a unique piece of Bristol’s social and cultural history. Well over 100 years our members’ weights are recorded here, including the Daveys (tobacco), Harveys (sherry), Averys (wine), Ways (Ashton Court)- and those are just the Leigh Woods residents.

The concept of weighing scales in a club setting began in India, when the huge “gymkhana” clubs started popping up in the mid 1800s. Members would often weigh themselves before and after a meal, a quirky bit of boyish humour which then spread to clubs in the UK (East India Club, Boodles, National Liberal Club, to name a few). Naturally, the vast RAC on Pall Mall continues to have a number of scales on the premises.

Note 2024: At the time this house history was drafted, 2020, the scales had been out of action for four years. They were subsequently restored by JJ Scales of Bristol who kindly halved their fee. I was pleased to be part of the “Weighing Scales Task Force” which saw this important object restored and put back to use.

Arthur’s name appears in numerous places within the original weights register, with his weight varying between 12 and 13 stone. This does little to add to our picture of Arthur’s life, apart from confirming that he – like some other Ways and Sampson Ways – was almost certainly a club member in his own right. He is also accompanied in the book by other Leigh Woods residents from the time, including the Daveys, Harveys and Averys.

Weights of Arthur Edward Gregory Way (source: Clifton Club “weighing machine register”

1883 – A E G Way – 12 stone, 12 pounds

Edgar Way 13 stone, 11 pounds (also in the club that day, 2nd December)

1885 – A E G Way – 13, 5 pounds

1891 – A E G WAY – 13 stone

Extensions, Heraldry & A Mysterious Fireplace

Of all the property’s former tenants, it is the Ways that have left their mark most clearly. The “W” inset on a shield attached to the main staircase refers to their surname. The arm holding a baton on the opposite bannister is derived from the family crest and literally means “the way”. In medieval times, a man holding a baton would have shown “the way” for marching armies.

Highly decorative newel posts were a popular addition to late Victorian homes. The winged lions which hold the shields on the staircase are the heraldic symbol of Saint Mark, but it is unlikely that this connection is intentional, winged lions also being symbols of majesty and strength.

The full crest also shows six fishes, and you can see these on hybrid Way/Smyth shields in the Ashton Court mansion and adorning Church Gate (the lodge building facing towards All Saints Church in Long Ashton). Sadly the arm holding a baton did not make it into these hybrid coat of arms and it is worth noting that these shields are really embellishments made by the family, rather than a formal coat of arms registered with the College of Arms in London. Interestingly, a large number of these appear to have ended up in a house in York – full details of which can be provided by the Malago Society. The family motto that accompanies it is “fit via vi” or “the way is strength”, another play on “way”.

There is a helpful article on Ashton Court’s heraldry on the Friends of Ashton Court Mansion site. This shows the “Smyth impaling Way” coat of arms on display in a window above the staircase adjoining the Great Hall.

Strangely, the surname does make an appearance in the family’s pet cemetery, situated at the front of the main Ashton Court house, where more than one dog was given Way as a surname. Igor Kennaway told Bristol Museum (OH573): “There’s a dog here, that’s actually got the surname of the family, Sonia Esme Way. Now I find that really creepy, I’m sure that’s one of Dolly Way’s dogs, because she looked upon her dogs as her children.”

The Ways are also responsible for the mock Tudor extensions to the dining room and living rooms. Both exhibit mock arrow slits to the exterior as well as shields. The dining room retains Corinthian columns and large fireplace which bares Arthur’s initials. Both inglenooks created by these extensions have been retained. They also added the castellated bay window and cornicing to the living area. It is highly likely that the shields on the exterior of the property also once held his coat of arms, a normal practice for Victorian families and something we can see at other houses nearby.

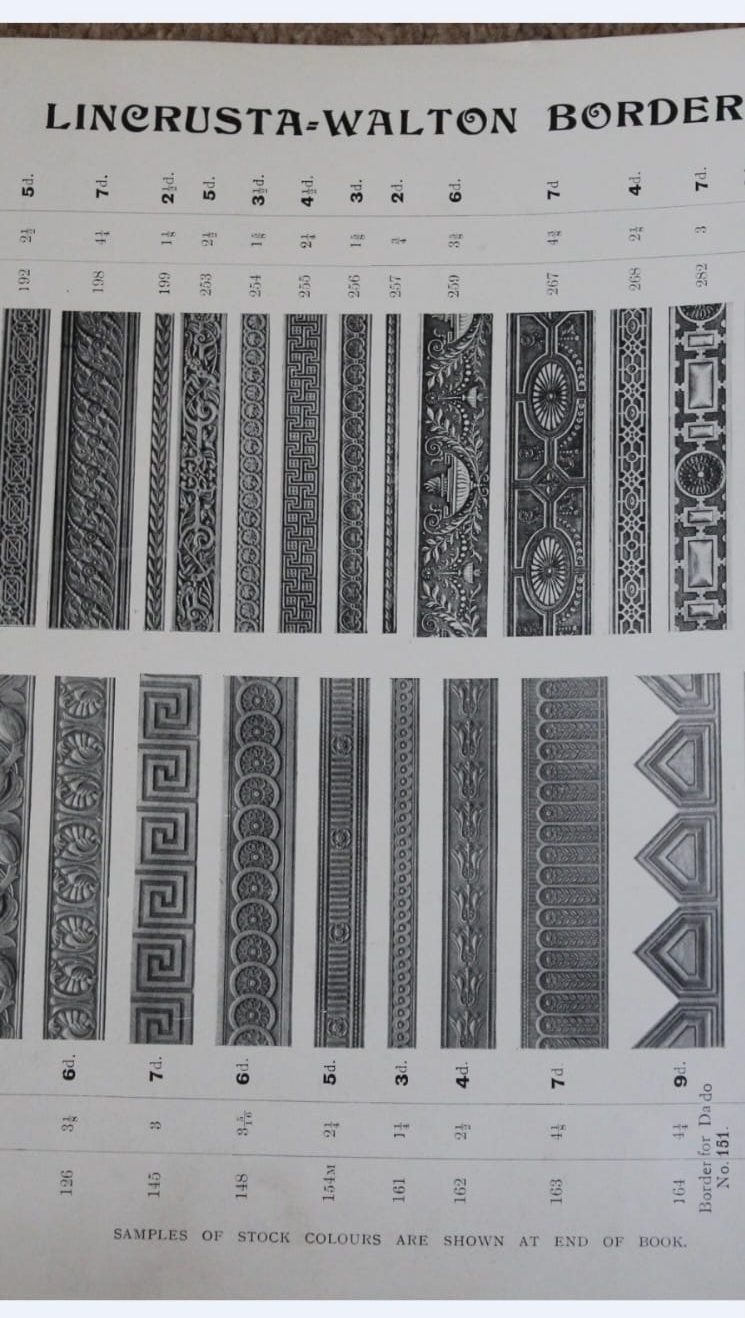

Update 2025: During restoration works following a major flood, the cornicing in the living room needed replacing. This was found to be 1898 Lincrusta borders, example 148 in the brochure above. Sadly the roller that produced it was melted down in 1939 to provide metals for the war effort.

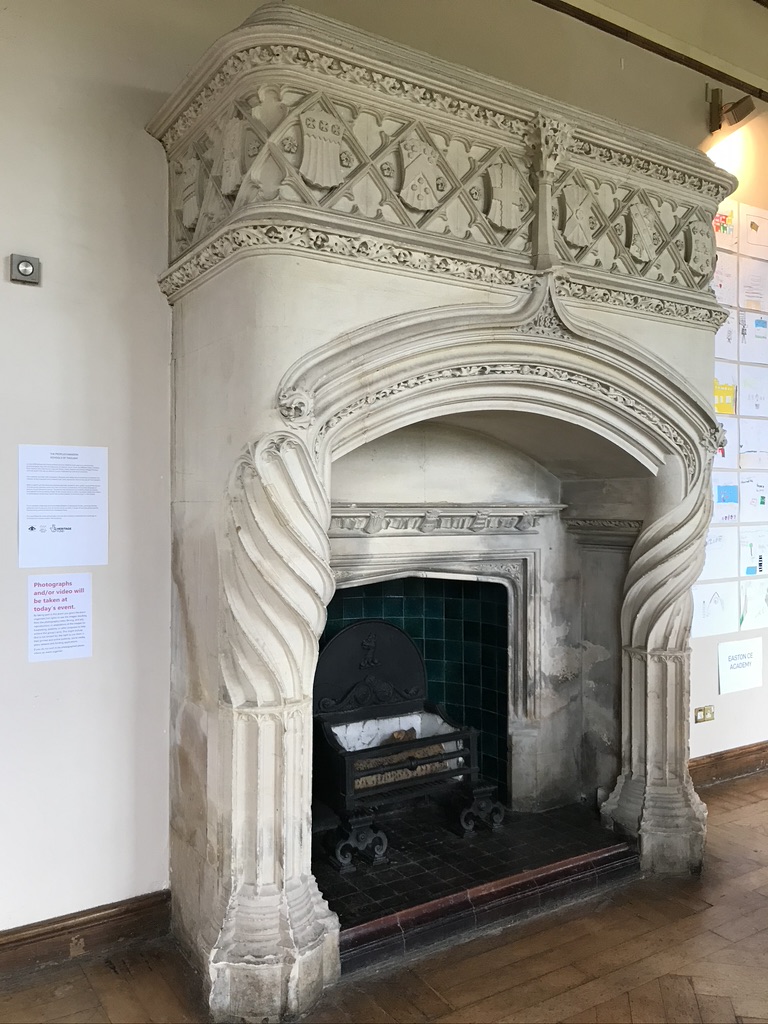

The Ways probably also extended the property (with the cheaper uncut stone work) to include what is now the kitchen, and installed the 1653 fireplace in the hallway, which may or may not be a genuine 17th century fireplace moved from another property. Further research is required to ascertain this. It bears the initials “H D B”. One Hugh Smyth owned the Ashton Court estate in 1653 – so the H may be from him but it is not obvious what the other letters would indicate. Another line of enquiry – that the B would be for Butterworth from the side of the family that Ada and Arthur both shared as cousins – did not show up any obvious results. There were H Butterworths around at the time but the trail becomes very hard to trace.

These features give us a clue as to how the rest of the house might have looked at the turn of the last century. It was probably, like Ashton Court at the time, far fustier that it is today with a darker interior and much more ornamentation. Tyntesfield is probably the best nearby indicator of the styles of the time.

Arthur Way also left a visible mark on Leigh Woods itself. In 1890, Way offered up £1000 for the construction of what is now St Mary’s Church, on the condition that construction began without delay. That represented one fifth of the funds needed to build the church, around £82,000 in modern money. The Leigh Woods Society notes: “He must have been helpful in getting the necessary permissions from his cousin, who was patron of the living in Long Ashton from which the new parish was to be cut.”

He would also have had easy access to the church at the time, via the end of his garden. Images of Emily Way laying the foundation stone, with A E G Way alongside, feature in the church vestry.

On the opposite side of Bristol, another branch of the Way family were undertaking their own building project – the construction of Berwick Lodge, now a luxury hotel. General and Mrs Sampson Way built the property for their daughter Rowena Way as a wedding present.

The Victorian Household and Leigh Woods at the Turn of the Century (1901-1919)

The 1901 census also shows that a number of famous Bristol names were in the area, notably the Averys (of Averys wine), Harvey (later of Harvey Bristol Cream), Davey (tobacco) and also the Wills family (Wills tobacco) who later bought Nightingale Valley and gave it to the National Trust. The Way’s immediate next door neighbours included the acclaimed naturalist Rev Thomas Hincks FRS (responsible for describing 360 invertebrates amongst other accomplishments) and the architect Samuel Coleman, who designed part of what is now Clifton High School, a lecture hall for the University of Bristol and several churches.

By 1901, the household staff had again changed with five permanent employees. Sarah J Nichols, the 31-year-old housemaid, was originally from Westerleigh, Gloucestershire. Frederick M A Smith is listed as a manservant and was 39-years-old. Ada G Smith. There is now only one groom, a Richard J Harris, aged 19 years and originally from nearby Abbots Leigh. Jane Sutton is the youngest servant, aged just 18 years and listed as the kitchenmaid. At 41 years the cook, Elizabeth U Linkham (from Swindon), is the oldest employee.

The census also lists a number of visitors, 47-year-old Sarah Cooper and 36-year-old Ada G Smith are both listed as hospital nurses, continuing in a long line of nurses that seem to be continually present at the property. Without direct contact from the family it is not easy to ascertain what happened to the Way marriage. It is obvious that the Ways did not have children. Ada is listed as having being “hip joint lame” in the 1901 census, and is absent from the 1911 census, where she appears to be living in Oxfordshire with three servants.

By 1901, Greville Smyth has passed away, leaving the estate in hands of his wife, Emily. Her efforts on the estate led to both a damehood, and a park named in her honour, which remains Dame Emily Park at the time of writing. She was included in Jane Duffus’ Women Who Built Bristol 1184-2018 (Tangent Books), where her entry notes her major donations of land to the City Council, her taking on the duties of a head of household after the death of Greville and her generosity towards the poor. Her role in establishing the Bristol Museum of Natural History is noted above. Emily passed away in 1914.

As noted above, the Smyths owned large tracts of Bedminster and Southville, much of which was used for coal mining, which expanded rapidly as a result of the “coal rush” in the 1800s.

From Know Bristol (2022): Coal mining was one of the most dangerous jobs of the day and it is often said that as many as one man per month died operating the mines of South Bristol. The Dean Lane Colliery was one of the largest in Bedminster in the 19th century, with a total contingent of around 400 men at one point. On 10th August 1886, a gas explosion resulted in the death of one man who fell into the pit and the suffocation of nine [others]. The youngest was John Brake, who was only 14 at the time.

It is this park, the site of the tragedy, that is now Dame Emily Park, a concrete hexagon marks out the site of the main shaft.

Arthur remained at the house, where by 1911 the household had grown to eight people, including a hospital nurse (36-year-old Helen Frances Campion) and a lady housekeeper (Jessie Margery Featheringham, a married 26-year-old from London). Neither have listed themselves as employees or servants.

The house had a new butler, Egbert Tom Parsons, originally of Blackwell. Egbert Tom Parsons signed up to serve in the Royal Army Service Corp during WWI. Records show he was at Huddersfield War Hospital for a while and was able to claim additional pensionable income after the war on account of having aggravated asthma. He had married Mabel Brown in 1912 and was formally discharged in 1919.

The youngest employee in 1911 was the kitchen maid, May Baufield, aged 17 and from Somerset. A 25-year-old Cardiff-born Fanny Clark is now the housemaid, along with a 47-year-old Fanny Collins. The domestic cook is now a Sarah Jane Boyd, originally of Durham. Apart from Arthur and Jessie, all the staff are listed as single. Notably absent from this census are the staff previously employed to look after horses (and presumably also the dogs).

One unexplained object is a postcard dating from April 1907, found on Ebay by my aunt. It indicates a Mr Edward Davenport as being at this address. The postcard reads:

“Dear Edward

Sorry to have kept you waiting last evening, but had to go to St Adians Vicarage and did not return until 6.30 will see you tomorrow at 12.40.

Yours Sincerely, Fred

There is no record of any Davenports having lived here but it is possible he was a guest of Mr Way.

There were also movements next door at Stokeleigh. On 8th January 1916 – Elizabeth Hincks died and on 23rd February 1916 one John Kenrick Champion (and a Charles Muller) became owners via probate. On 17th May 1916 – William Ernest Fursier (warehouseman) purchased the house. The Fursiers remained at the property right up until 1955, with records indicating that N B Fursier died at the property. Curiously, on 27th May 1953 Nellie Fursier purchased the grass verge in front of the house from the Leigh Woods Land Company, showing the firm still going almost 100 years later.

W E Fursier died on 5th February 1940 and it appears the property ends up in probate to William Leonard Samuel Vassall. It is William that assents for the property to go to a Nellie Blair Fursier. After her death it was bought by 1955 – John Esmond Cyril Clarke. J E C Clark pops up all over Bristol’s 20th century history, including a spate as one of the last Secretaries of the Commercial Rooms (formerly a private members’ club, latterly a Wetherspoons, on Corn Street) in 1948.

He was later Master (1956) and Treasurer (1969–1982) of the Merchant Venturers, also Chairman of the Clifton Club (1960-64). A tree opposite Merchants Hall commemorates his life.

The Hunting Lodge Rumour

In summary, it would be fair to say that the house would have been quite an eccentric place even by the standards of the day. Living off income from the Ashton Court estate, Way would have been able to indulge his interests much like his first cousins were doing over at the estate itself. It held onto more land than the surrounding properties, kept more horses and dogs, and had an area for entertaining gypsies.

The animals probably contributed to the idea that the house was a hunting lodge. So persistent was this idea that the house was marketed by Savills as a former Smyth hunting lodge back in 2003, with the room built for boxing and gypsies suggested as a place where dead animals were hung after a hunt. This seems unlikely. With access to his cousin’s estate and its shooting parties, and potentially those of the other large estates around Bristol, it makes little sense to operate a hunting lodge from suburban Bristol, even if it is the outermost edge of suburban Bristol. Nightingale Valley was owned by the Leigh Woods Land Company from the 1860s onwards, through to 1909 when it was taken over by the Trust, so there is little chance that hunting parties were going into the woods at this time. Nevertheless, the property would have resembled a sort of country house setup in a suburban setting but quite how this might have looked and sounded in practice will difficult to ever fully appreciate.

Another unsubstantiated claim from the 2003 Savills brochure is the idea that the Averys lived here. The exact words are: “[the house]..was extensively refurbished in the 1920s by the Bristol Wine Merchant family – the Averys when it was adapted for more modern day living”. There are no records of the family ever having lived here.

Far more likely is some local confusion as to where they did live in Leigh Woods – The Evergreens on the A369. One Joseph Avery lived there with his wife Frances Strangeways (nee White) along with their son, Ronald Avery. I am told the property was a wedding present.

Nightingale Valley is saved (1909)

On 15th May 1909, George Alfred Wills donated Nightingale Valley (80 acres) to the National Trust, having purchased the site from the Leigh Woods Land Company. In so doing, he saved both Stokeleigh Camp and what is now the Leigh Woods National Nature Reserve, from development. He would later donate most of the grounds of his own house, Burwalls to the Trust, which also remains part of the Leigh Woods National Nature Reserve. It was an extremely important moment both for the local area and for what is now the River Avon Area Site of Special Scientific Interest.

The indenture reads as follows:

Indenture Of Conveyance dated the 15th day of May 1909 between the Leigh Woods Land CO. Limited of the one part and George Alfred Wills of the other part witnesses that the said Company in consideration of a certain sum of money paid to them by the said G.A. Wills sell and convey to him his heirs and assigns the estate above named.

And whereas the said G. A. Wills is desirous of vesting the said hereditaments in the National Trust for Places of Historic Interest or Natural Beauty in order that the same may be held for ever for the benefit of the Nation in accordance with the National Trust Act of 1907.

Now this Indenture witnesseth that the said G. A. Wills conveys unto the National Trust all those lands, hereditaments and premises containing by estimation 80 acres and 22 perches, formerly part of the Leigh Woods estate, situate in the parish of Long Ashton co. Somerset comprising Nightingale Valley and part of the hanging woods all which premises are delineated on the plan annexed to hold the same in accordance with the Provisions of the National Trust Act of 1907 for the reason able benefit of the public subject to such regulations as the Council of the National Trust and the Committee of Management of the Leigh Woods constituted by an Indenture of even date herewith may from time to time think proper. In witness whereof the said G. A. Wills has here unto set his hand and seal and the National Trust have caused their common seal to be affixed.

Signed sealed and delivered by the above-named George Alfred Wills in the presence of E. J .Swann, J P and Henry Napier Abbot

Parting Ways (1919-1936)

The Ashton Court estate continued to downsize during the late 1800s and early 1900s. Anton Bantock attributes this to the lavish lifestyles of Arthur Way’s cousins as well as “a decline in farm rents, industrial troubles in the coal pits, super-tax, tax on land values and death duties”. By 1946 the estate was functionally bankrupt. What Arthur would have made of this we can only speculate. We know that his father was considered an effective manager of Ashton Court’s assets and it is possible that his successors weren’t able to keep control of the finances in the same way. It looks as though Arthur himself may have been in charge of the estate’s finances for a time. But the decline of Ashton Court, and the reasons for it, are similar to what we can see having happened at a number of large and often very ancient estates in England over the same period.

Arthur Way died on 22 February 1919, leaving his estate to Ada. His wife then appears to have moved back to the house, where she stayed until her own death in 1936. There was a brief period during this time when Ada and her staff could have taken a train from the bottom of Nightingale Valley. A GWR station opened there for just under four years, 1928 to 1932 but was closed due to lack of traffic.

The 1921 census shows Ada is back at Woodleigh, with four servants. These were Emily Collins (58, from Westbury-on-Trym, unmarried), Annie Yeoman (44, also of Westbury-on-Trym, umarried), Sylvia Herington (20, Westerleigh, unmarried) and Frederick Spiker (59, from Warwickshire). Spiker was, in all probability, the property’s last true butler, whilst Emily Collins listed herself as a cook as well as a house maid.

Ada’s funeral was held (appropriately) at St Mary’s in Leigh Woods and was covered in the Western Daily Press in some detail. One Rev C P Way, formerly of St Mary’s, Henbury, conducted the service and a long list of Ways attended as well as Butterworths, Sampson-Ways and members of the Miles family. Both Arthur and Ada are buried at All Saints, Long Ashton (not to be confused with All Saints, Wraxall). They lie a few feet away from Greville, Emily and Esme Smyth in the centre of the graveyard.

It had been thought their grave was unmarked – the church’s map shows only that they are in plot ACE but – having gone there myself – Ada and Arthur both have a single tombstone, next to the Smyth tomb. Arthur simply has his date of death on the stone while Ada has “an absolute saint” inscribed on hers.

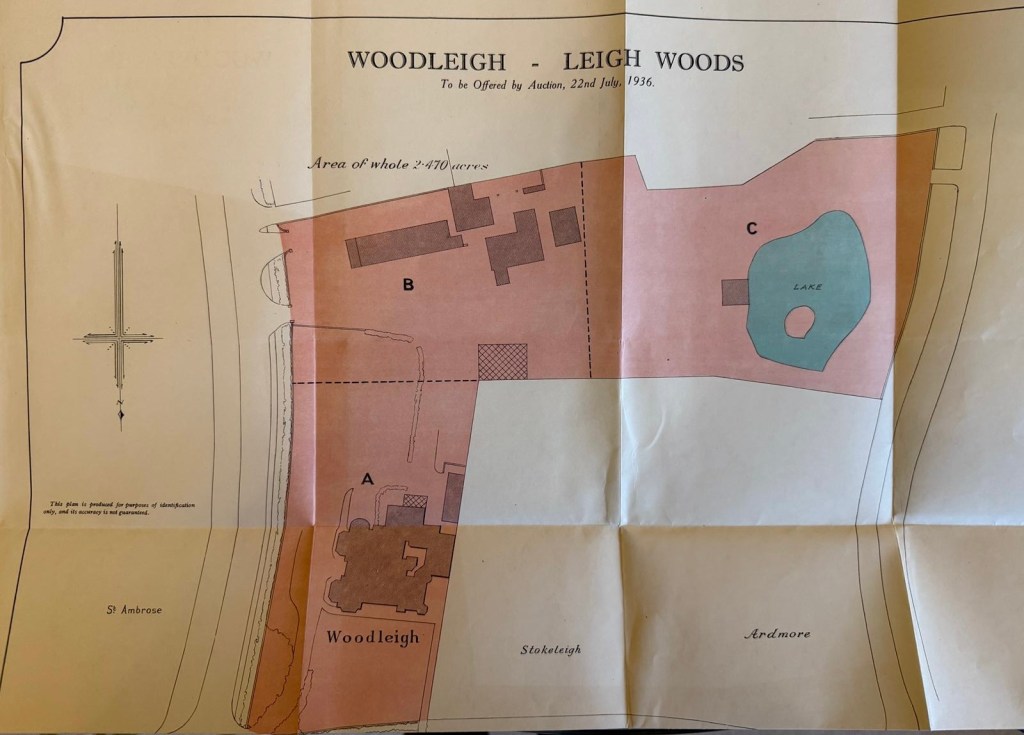

The beneficiaries in Ada’s will (William Henry Greville Edwards, Henry Thornton Locock, William Langham Carter) sold the property to Roy and Eugenie Boucher, who retained the plot with the lake and constructed a property there. Barbara and Stuart Evans purchased the plot that included the main house. Curiously, it appears that William Henry (1856-1940) was the son of George Oldham Edwards and Emily Way. We encountered George earlier as a director at the Leigh Woods Land Company and Emily’s first husband. William was High Sheriff of Bristol in 1903 and lived at Butcombe Court. She left an estate worth £134,035 in 1936 values.

William Langham Carter had married into the Butterworth side of the family in a 1902 wedding at Bath Abbey, to one Frances Maud Butterworth. He appears to have worked for the Straits Settlement Civil Service (Singapore).

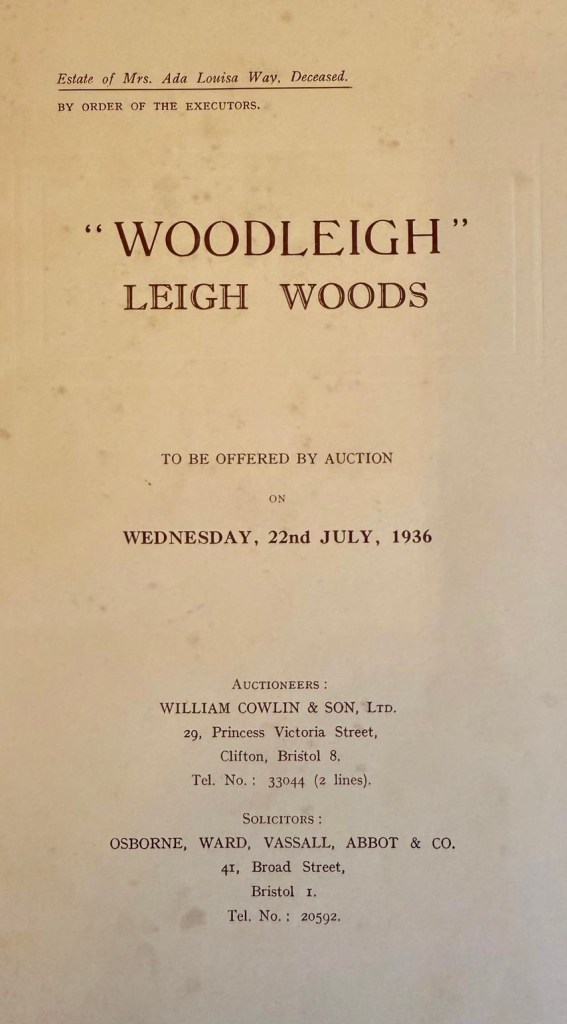

The executors of Ada’s will put Woodleigh up for auction. The auctioneers were William Cowlin & Son Ltd (of 29, Princess Victoria Street) and the solicitors were Osborne, Ward, Vassall and Abbot (of 41, Broad Street).

The auction pamphlet provided by Cowlin provides a remarkable window into the condition of the estate in 1936. The house is marketed as having “gardens of rare beauty with tennis lawn, boating lake, island, thatched boating house, flower and vegetable garden” and 2.5 acres of land in total. As might be expected, various rose gardens, rockeries and oaks are mentioned.

Importantly, the fireplace is noted as having been antique, rather than a Victorian folly. We can’t know for sure of course – Cowlin may have been no better than Savills when it came to historical accuracy – but it does suggest it may well be a genuine 1600s item.

In a difference with today’s property, the dining room is said to open out onto a “varandah”. It is clear where this door once was and had this been retained, it may well have made the front of the house feel more connected with the rest of the property than it does now.

It also mentions a “third sitting room” with “oriental carvings” that opens out into a grotto with fountain. The grotto and fountain are no longer in place but the suggestion of a grotto adds to the strange image of this suburban property operating as an aristocratic residence in miniature.

Cowlin understandably makes a big sell of the property’s lake. Today this is the lake that sits in the grounds of the Lake House on Vicarage Road. It is not clear whether this was installed during Arthur Way’s time or if Ada put it in but it is clear that it was well maintained during her final years at the property.

It came with a “large timbered and thatched boat house”, a pergola and an island, the latter still exists to this day. Included in the sale was a Gardener’s Cottage, which came with a living room, scullery and 2 bedrooms. It was let to a Mr Bass.

The immense structure in the garden that shows up in the 1940s map is confirmed as a very large greenhouse, oddly situated close to the house.

It was sold on 22nd July at the Grand Hotel on Broad Street.

The Ways continued to feature in Ashton Court life right up until the death of Esme Smyth in 1946. The city council purchased the estate in 1959. The grounds have become a hugely important local asset, used by thousands of Bristolians every week (and around 1.6 million per year) for their leisure. It is also the site of the annual Bristol Balloon Fiesta. The house itself has gone through peaks and troughs, in terms of usage, the financial picture, and its overall condition. The mansion is a problematic site to manage and when this project was originally being drafted (2019), the entire upstairs was completely derelict (see images below).

The Sampson Way side of the family was also prominent in Bristol life at this time – one Major General Sampson Way became chairman of the Clifton Club 1939-40.

Page Citation: Coates, Ashley. “The Way Era (1880-1936).” A History of a Bristol House, ahousehistory.com, 1 Mar. 2021, https://ahousehistory.com/the-way-era-1880-1936/.